Kate Moore, UNSW

Urinary incontinence is urine leakage from a loss of bladder control that mainly affects women after childbirth. But it can happen to anyone. Around

37% of Australian women have some form of the condition compared to 13% of Australian men.

Mild incontinence is

the most common form, affecting about two out of three sufferers. This is where small amounts of urine leak out onto clothing a few times a week and require a light pad or pantyliner to catch the flow.

Subscribe for FREE to the HealthTimes magazine

Moderate to severe incontinence is less common and affects about a third of sufferers. Women need to use a specific incontinence pad (with absorbent gel) and change it more than once or twice daily. This might not be enough though, and they may get accidental wetting through to their clothing even if using the pad.

Whatever form it takes,

the impact of incontinence can be debilitating and women are often too embarrassed to seek help from their doctor. This is unfortunate as there is more likelihood of a cure for those who receive treatment at an earlier point.

Stress and urge incontinence

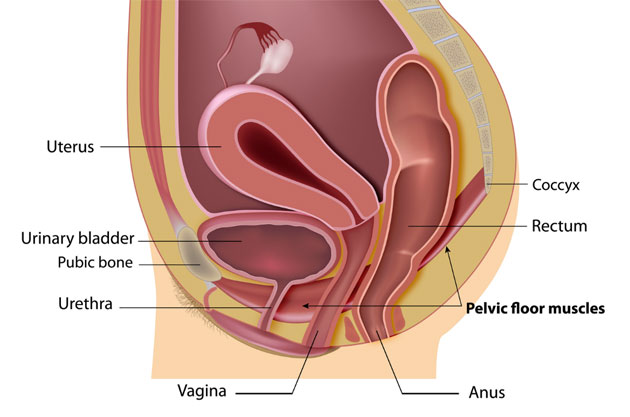

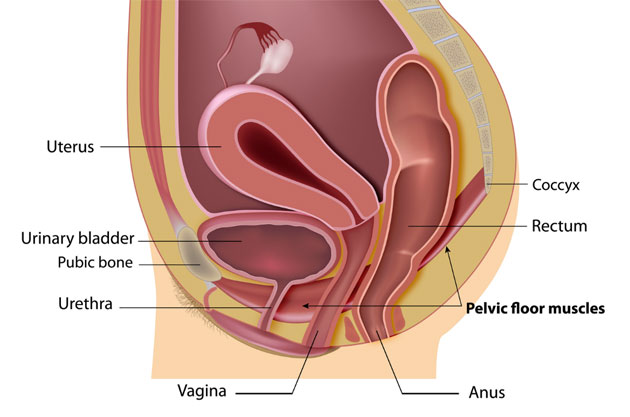

In stress incontinence, urine leaks out during coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercising. People with this condition have weak pelvic muscles around the urethra, which are overwhelmed during times of physical stress.

About 28% of young women who engage in high-impact sports - such as gymnastics, basketball and tennis - develop stress incontinence.

The second form, urge incontinence, is a desperate need to go to the toilet due to spasms in the bladder muscle. Sometimes this results in leaking. People often go to the toilet more than eight times a day, and get up to go more than once at night.

There’s another form called overflow incontinence, which is actually more common in men who have an enlarged prostate gland. It partly blocks the urethra so a pool of residual urine builds up in the bladder and leaks out when capacity overflows.

The problem is rare in women and happens when the bladder has

prolapsed or dropped down into the vagina. This can block off the urethra, leading to incomplete emptying with overflow leakage.

Incontinence across the ages

Women are more prone to incontinence because their urethra is very short (only 4 cm) while the male’s is quite long (11 cm). If you imagine a garden hose, the shorter it is, the more likely water from the tap is to leak out. In a longer hose, the tap water might stop flowing before it reaches the end.

About a third of women

who have had children suffer from incontinence at some point. Adolescent girls and older children also experience urine leakage, mainly in the case of bed wetting. This is due to an overactive bladder and

affects about 4% of children between five and 12.

Weak pelvic muscles around the urethra can lead to stress incontinence.

from shutterstock.com

Bed wetting gradually declines during adolescence, but urge and stress

incontinence persist in up to 10% of women. Incontinence then becomes more common after menopause as women

produce less oestrogen which weakens ligaments and pelvic floor muscles supporting the urethra.

Obesity

increases the likelihood of incontinence too, as abdominal fat puts pressure on pelvic floor muscles. Likewise, constipation and repeated straining to pass a bowel motion weakens these muscles,

increasing the risk.

Other factors influencing incontinence include urinary tract infection, which is

known to worsen its prevalence and severity. Anxiety also contributes to symptoms with studies showing 28% to 32% of women with

urge incontinence, and 22% with stress incontinence, suffer from anxiety.

Treatment options

Urinary incontinence implies lack of control which leads to feelings of shame and reluctance to seek help. As one

study showed 55% of women who wore pads for incontinence had not consulted a general practitioner in 12 months.

This is unfortunate as treatment options have advanced enormously in the last 20 years. If a patient seeks treatment when leakage is mild, it’s much more likely

to be successful. The more severe the incontinence, the more difficult and expensive it is to treat.

First-line therapy for stress incontinence is pelvic floor muscle training by a specialist continence physiotherapist, which doesn’t require a doctor’s referral. This has a 65% likelihood of cure for mild, and

35% for moderate, incontinence with no side effects or risk.

If this doesn’t work, there are two kinds of

vaginal ring pessaries available to support the urethra. These are particularly useful for women who only leak with active sports or gym classes.

The final option is to have an operation. The most widely performed is one where a mesh tape is placed under the urethra like a sling for support. About 93% of women

are found to be cured three years after having the surgery and it shows good long-term results.

For urge incontinence, first-line therapy is training to increase bladder capacity.

A tablet or patch that reduces bladder spasms is prescribed alongside training for at least three to six months.

Urge incontinence after menopause is treated with vaginal oestrogen cream that helps

strengthen the urethra and enhance bladder capacity.

About 40% of women who don’t respond to these are found to

have a low grade infection of the bladder, known as cystitis. More treatment options are being developed for this. For instance, a

randomised trial is currently underway exploring bladder-specific antibiotics together with a muscle spasm reduction tablet for urinary incontinence.

No woman should have to suffer urinary incontinence in silence or shame. The above treatments are not difficult, but they require a professional to steadily work through the options to find the right cure for each woman.

Kate Moore, Professor, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Head of Department of Urogynaecology, UNSW

Comments